On Mirrors and the Making of M’s story

By Laura Waddington

1. The confiding of a tale

M told me his story in Jordan, in 2006. I had travelled to Amman that summer to research a possible film about the war in neighbouring Iraq, and on my first day wandering through the city, I got talking to a young man smoking a cigarette on a balcony, who turned out to come from Baghdad and to have seen my film Border. Jumping up in excitement, he exclaimed, “But I saw your film, one night, by chance, I’ve dreamt of your images! I have to introduce you to some of my Iraqi friends.”

I stayed until mid-November. Every few days, more friends and acquaintances of the Iraqi people whom I came to know, arrived seeking refuge from the killings and chaos of Baghdad. As much as the terrifying anarchy of the present, they spoke to me of their fear that the horrors that ordinary people had endured under Saddam Hussein’s regime and the Western sanctions were going unrecorded, the traces that remained after all the looting and burning were being replaced by new narratives. Some said that Saddam Hussein had destroyed the soul of the Iraqi people. “If you really want to understand what is going on now, tell just one ordinary person’s story from that time,” insisted one of them.

One afternoon, an Iraqi friend took me to have tea with a young couple who had recently fled Baghdad. They were lively, very bright and humorous; I liked them immediately. As I was getting up to leave, the young man, M, mentioned that he had been imprisoned by mistake during Saddam Hussein’s regime and later kidnapped, again in error, following the American and British invasion. I sat back down. We agreed that I would record his story with my video camera’s lens cap on—no image, as he was frightened that his family still remaining in Baghdad would be killed.

There followed a glimpse into horror as he described, in precise and relentless detail, two years spent alone in a pitch-black cell full of water up to his thighs when he was a teenager soldier doing his military service, in Taji camp, a Republican Guard military base near Baghdad. The experience had unfolded without explanation, the days and nights only broken by sessions of torture. The sole question that his torturers (amongst them army officers whom he had been serving under) had asked him, over and over again, was, “What is your name?”

“And I was so lucky, it was nothing at all,” commented M, smiling, when he had finished relating his account. He was referring to the hundreds of thousands of men and women who are presumed to have perished inside Saddam Hussein’s prisons of whom there is no official record.

Before saying goodbye to M and his wife, I promised him that I would one day tell his experience in a film, without revealing his identity.

Later, I wrote in my diary:

What keeps working on me, as much as the horror of what M recounted, is his defiant laughter. His torturers hadn’t managed to reach his soul. But like all that transpired during those hours, in the small ground floor apartment, in which he related his imprisonment, it was beyond the reach of my camera, my lens cover on, to protect his identity. His tale demands its own visual language: images primitive, unadorned, fragile. But I am brushing up against the limits of what could or should never be filmed. Impossible to do justice to what he endured. Yet impossible to turn one’s back to it.

Two years later, when I returned to the region and explained to the Iraqi friend who had accompanied to meet M and his wife that in Europe many people had reacted with disbelief to my reports of my months away, questioning the veracity of M’s account, some accusing him of being “pro-American,” and that promised film funds had fallen away, it was the first time that I saw him get angry.

From top left to right: Recording with my camera‘s lens cap on, and window shot, Amman, 2006; Discussing M‘s story with the Iraqi friend, who had accompanied me to meet M, during a walk in a nearby country.

2. The limits of High-Definition cameras and inspiration from gekiga

If I didn’t find a way to depict M’s story in a film, it wasn’t only due to the denial that I encountered in the West or my unease at depicting torture. The new, small High-Definition cameras which had recently replaced mini DV1 with pre-fabricated choices and gleaming, fool-proof images, lent themselves to certainty and deliberate narratives, the polished digital veneer suggesting a control and mastery over a story that I didn’t possess when it came to M’s account.

There was little in their perfect, over-lit vision to evoke the limbo of a pitch-black cell, and to remind the spectator of the limits of what they were seeing; a flawed attempt to convey the anonymous testimony of a man who couldn’t be shown—unreliable, incomplete.

For several years, I went round in circles, trying among other things to work with found footage from the internet. One night, in Brussels, I had a dream that I was drawing M’s account. The next morning, I took a tram to an art shop. I bought two black pens and a small notebook and I began to draw. Not having drawn since I was a child, I imagined that my sketching was temporary, a few pages to give to an illustrator to carry on in place of me. But immediately I liked the improvised nature of the pen with its lack of claim to accuracy, and became interested in the stark gap revealed between M’s words and where my untrained line couldn’t go. Faced with the limits of my comic book-like sketches, I hoped that the reader’s mind would wander into the spaces between and beyond the images, to reflect on the zone of terror that M described alone.

First sketches for M‘s Story, most later rejected.

I had only read one graphic novel at the time. I turned my attention and soon my awe to gekiga, the socially engaged comics that had emerged in Japan at the end of the 1950s, characterised by their harsh themes, vivid black and white drawings, and cinematic techniques. Uncompromising portraits of the human condition, they carved out room between deceptively simple drawings and dark societal commentary for their audiences’ imaginations to go to work.

Initially I drew only with one type of black felt tip pen—I wanted to train my hand and eye to hone in on the essentials of M’s account. As I progressed, I began to conceive of the abstraction of black and white and the detailed, at times, decorative style of my drawings, as a way to gently lead the reader into the cell and gradually expose the horror, in a manner that I believe would have been unbearable were it depicted in colour or video. But I was constantly confronted by the inadequacy of my response.

One challenge, aside from not knowing how to draw, was how to convey suspended time: the years that M spent stuck alone in a dark cell full of water, without any visual cues to mark the passage of day to night, with no understanding, on his part, of why he was there, and no end in sight.

The friend who had accompanied me to meet M and his wife later mentioned that the absurdity of M’s mistaken predicament felt like a mirror of what had been done to the Iraqi people during Saddam Hussein’s regime and the embargo. Of those years of sanctions, he said: “It was as if the present had been cancelled, everyone lost in memories of their past or in small dreams of a future that couldn’t unfold. No one knew when it would end . . . nothing was possible.”

Hell by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, who is widely credited as the creator of gekiga. Set in the aftermath of Hiroshima, the tale tells of the treachery and duplicity of a photo taken at the site of horror.

3. Daesh and the changing landscape of violent images online

It soon became apparent that the book would only ever be a record of my failure to depict the subject of torture. Sometimes I found myself burning and tearing into the drawings and integrating this into the book. I think it was, in part, a reaction to the horrific images of state torture and violence that I found online, including chilling footage of executions and punishments recorded by Saddam Hussein’s fedayeen to sew fear in the Iraqi population; or the propaganda and other clips that were being uploaded to the web almost in real time in the years before and while I drew by American occupying soldiers and Iraqi insurgents. Concealed in my torn pages was anger and alarm at where these dark corners of the internet suggested that our relationship to images was heading; the implications of a new visual and technological landscape for which the world felt totally unprepared.

While I sketched, the gruesome snuff videos of ISIS began to appear (certain high-ranking officers of the disbanded Iraqi army had just been biding their time, as a number of Iraqi refugees in Jordan had predicted to me). Whether we refused to watch their images or not, they seeped into and diminished us by their mere existence; we hadn’t developed any strategies to resist them. Their videos, unseen by me, still wove their way around the edges of the book leading me to question at every turn what separates one obscene depiction of horror from another, if anything. The only antidote seemed to be slowness and difficulty, working alone on a hand-made image, albeit clumsily, for days.

4. Taji and the satellite images, that paved the way for war

M had explained that his dual experiences of mistaken identity (the imprisonment in Taji camp under Saddam Hussein‘s rule during the embargo, and his kidnap in Baghdad after the American and British invasion), felt like the mirrored image of separate regimes, two sides of a same face. If he had had hopes for the invasion, it was now nafs al shi, the same thing, he said. All this, a mirror of what had been done to his country.

There were questions that I had been asking myself ever since hearing M’s account, and that returned often as I drew. What is a complicit or manipulative image and what is its opposite? Is complicity latent in certain images and subjects, or conferred along the way, in small parcels, by the filming eye, the technology, the editing, the observer, the context in which it is shown? Is there a way to shed it by creating a distance inside an image or does this merely re-enforce and reactivate it? In walking away from my camera and teaching myself to draw from scratch, I had been hoping to edge a bit closer to finding out.

The questions around the manipulative potential of images had first found their way into my mind years earlier with the spectacle of Operation Desert Storm (in the Gulf War of 1990-1991), with its sterile targets and precision military images beamed nightly onto our TV screens, and that clip that marked the end of the conflict: a helicopter shot of thousands of retreating Iraqi army tanks and trucks, buses and cars, shelled and abandoned on a desert highway, not a soul in sight. But where had all the Iraqi soldiers inside their burnt vehicles gone? When the war vanished from our imaginations, the absent image remained, throwing into question all the images that I watched (or would come to make) after.

And while that theatre of the Gulf War of 1990-91 had drawn to a close with a silent absence from an aerial shot, the next war would be ushered in with an argument constructed around an absence from an image: a decontamination truck missing from a satellite shot filmed above the military complex at Taji…

I retrace the line to 5 February 2003. On our computer and television screens, the U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell is making his infamous address to the UN Security Council, arguing to the world the case for invading Iraq:

“Our sources tell us that, in some cases, the hard drives of computers at Iraqi weapons facilities were replaced,” he says. “Who took the hard drives? Where did they go? What’s being hidden? Why? There’s only one answer to the why: to deceive, to hide, to keep from the inspectors. Numerous human sources tell us that the Iraqis are moving, not just documents and hard drives, but weapons of mass destruction.” He goes on: “Let me say a word about satellite images before I show a couple. The photos that I am about to show you are sometimes hard for the average person to interpret, hard for me. The painstaking work of photo analysis takes experts with years and years of experience, pouring for hours and hours over light tables. . .”

Then he proceeds to project a satellite photo of a stretch of barren land dotted with grey square-shaped mounds and a network of roads in a place called Taji (red and yellow shapes drawn around the mounds indicate the presence of munitions bunkers).

The first satellite photo of Taji shown by Colin Powell to the UN Security Council, February 5, 2003.

The second and third satellite photo of Taji shown by Colin Powell to the UN Security Council, February 5, 2003.

Next, Powell shows to the chamber two aerial photos side by side. The image on the left of the screen is an extreme close-up of one of the square mounds from the previous satellite photo. A label identifies it as a “Chemical munition bunker” and another label indicates the presence of a “Decontamination vehicle” nearby. Powell explains that the vehicle is in the habit of moving back and forth between the four chemical bunkers at this site. He says that the vehicle constitutes a “sure sign” that the mounds are active chemical munitions facilities with people busy working inside them, the truck at the ready in case something goes wrong.

We do not actually see the vehicle moving around because these are still images and we do not see inside the bunkers nor any people.

The third satellite photo, on the right of the screen, is a medium close-up of a section of the same stretch of land a few weeks later. At the bottom of the frame, we see convoy of vehicles driving along a road: United Nations weapons inspectors on their way to make an inspection, Powell explains, and above the road, are two solitary square mounds without the presence of the “Decontamination vehicle.” This absence of the vehicle, Powell claims, is proof that the bunkers at Taji have been sanitized in preparation for the weapons inspection and that Iraq is in the process of concealing weapons of mass destruction from the UN weapons inspectors. “What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence,” Powell declares.

“What is Taji? Just a blind spot on our almost non-existent mental map of a country,” I thought as I stared at those vague images on my computer screen that day in February 2003, and took in Powell’s slippery argument and leaps of logic. And a shiver, perhaps a premonition, shot through me.

It is at this moment—of Powell’s words about the images taken over Taji—that I have the impression that our ability to trust in truth and our own perceptions in the West begins to break down, and that it will not fully return.

Invited to tea with M and his wife, in Amman three and half years later, l learn that the site of his mistaken confinement and torture, happens to be the military base at Taji.

5. The papers littered on the ground at Taji and what versions of history filter through

At one point, during their subsequent occupation of Iraq, the American authorities rename the former Iraqi Republican Guard military base at Taji. They call it Camp Cooke, before changing their mind and reverting to the original Arabic name, Taji. In the photos that I find that U.S. soldiers stationed at the occupied base, post online in the years before and while I draw, I come across an abandoned lavatory packed with a sprawling mass of discarded ring binders with Arabic writing on their labels and crumpled pages and damaged records piled knee high, all covered in thick layers of brown sand dust extending across the entirety of the room. The word Kafir (infidel) has been graffitied on an adjoining corridor wall by retreating Iraqi Republican Guard soldiers or maybe the looters who came after them. And there are numerous loose papers and defaced documents scattered on the ground throughout the ransacked facility, amidst debris and shattered glass (the uploaded images too blurred or low quality, in most cases, to establish more.)

Abandoned Iraqi Republican Guard documents inside a looted and occupied Taji camp. Re-filmed from US soldier‘s online posts.

As I sketch, I contrast in my mind the satellite images of Taji, projected to the UN in 2003 (images for which we went to war, leaving anywhere between a few hundred thousand and one million two hundred thousand Iraqis dead—no body count has been universally accepted), with the jettisoned documents scattered around the occupied camp that I zoom in and out of online, and the anonymous testimony that I am attempting to draw of a man whose face cannot be shown (and whose job it was during his military service at the base to type up database files). Were any records kept of the two years that M spent inside the pitch-black cell, while mistakenly suspected of smuggling military maps to fighters in Kurdistan, or of the other prisoners that he encountered there? I think to myself that if there were, they could well be amongst the forsaken records now littered on the ground.

M told me that he didn’t know what had become of his torturers, several of whose names he disclosed in the course of his tale, (he presumed that some or perhaps all of them had been killed in in the war). Before taking leave of his wife and him, I asked if he would like me to keep his torturers’ names in my eventual film. Standing by the door of the small apartment, a warm smile crossed his face and he answered yes, as if the telling would be a small kind of justice.

The naming of M’s torturers was, to my mind, a justification for re-telling his tale in images. If there is unavoidable obscenity in the act of portraying torture, I felt that the disclosure of the perpetrators’ names balanced it out and was necessary. Without the intention to name M’s abusers, perhaps I would have renounced the project early on, when I wasn’t able to find a way or the funds to depict his story in a film. That’s to say, the current hand-drawn tale is a project un-moored.

It was during one of my regular online searches for material about Iraq, in the years after meeting M, that I discovered that the man whom I understand to be the officer whom I have called “Commander X of the Republican Guard” was now living in Amman and being consulted in depth by the Americans. In the years that followed, Commander X would be interviewed on international television and quoted in The New York Times. No uncomfortable questions asked. He was useful.

Having torn up the contact details of M and his wife in the hours after our encounter in order to protect their identities, I had no means of getting in touch with M to ask him what he would like me to do. Bearing in mind his request that I not reveal his name or face out of fear for the safety of his family remaining in Baghdad, I made the decision to err on the side of caution. The traces of his torturers’ identities were removed from my original documents, and in the book the men are nameless.

Sketch of Commander X, along with other sketches that didn‘t make it into M‘s Story.

Whose version of history survives and filters through to us? Whose voices are considered worthy of record?

Which documents stay littered on the ground, trapped in a suspended space, as if mirroring the countless victims of the Iraq war who inhabit the in-between zone of a death toll that has never been officially agreed upon, or the hundreds of thousands of men and women who disappeared inside Saddam Hussein’s network of prisons and torture before them?

A partial version of Iraqi history in the West today is based on intensive recordings made with a man whom I understand, wrongly or rightly, to be the officer who forced M to eat dust and stones. . .

All that will officially remain of M’s mistaken torture are some flimsy drawings by an untrained stranger, a record that I later realised was unpublishable in the West. In looking into M’s tale and Taji, I had the impression of looking into a black hole.

Drawings of a ransacked Taji camp, that I based on photos that American soldiers uploaded to the internet during their occupation of the site beginning in 2003. On the bottom right is the ‘Most-Wanted Iraqi’ playing card for Ali Hassan al-Majid (Chemical Ali), whose headquarters were located at Taji.

6. Slowness that shaped the book. Strips on the ground

I had thought that the book would take a few months to make but it took years due to my slow process. Lacking experience, I’d sometimes stumble drawing basic things. Then I’d have to put the book aside for a few weeks and observe the detail or something similar, in real life or in films, until I’d learnt to sketch it. Other times, on getting to the end of a harrowing scene, my hand would shut down and refuse to draw. During those breaks that sometimes lasted several months, my brain acted as if the book had never existed, and as if I had never been to Jordan and heard M’s story. Months or weeks later, I’d sit down at a desk and still without thinking, take out a sketchpad and pick up where I had left off. The truth is I was too cowardly to confront M’s tale in anything but fragments.

Still, I have never known a project to encounter so many interruptions. Aside from major life events getting in the way, the pages survived floods, a roof caving in, the ransack of my home and more—luckily only preparatory and early drawings destroyed. (In the case of the intrusion, several tins of sketches that I had been unable to fit into a safe along with hundreds of the drawings were stolen, to be later recuperated in an Arab cafe in Brussels by a helpful contact—an episode which I cannot elaborate on; a hard drive containing part of my research about Iraq was never found). When my house became unliveable, I set off around the world, living out of a suitcase for a few years, continuing to draw in intensive stretches.

Why mention mundane incidents? Luxury hurdles in the context of M’s story. The disruptions, with their abrupt halts and starts shaped the somewhat disjointed form and style of the book, and when I thought the project was over, the longest of interruptions led to an unexpected outcome:

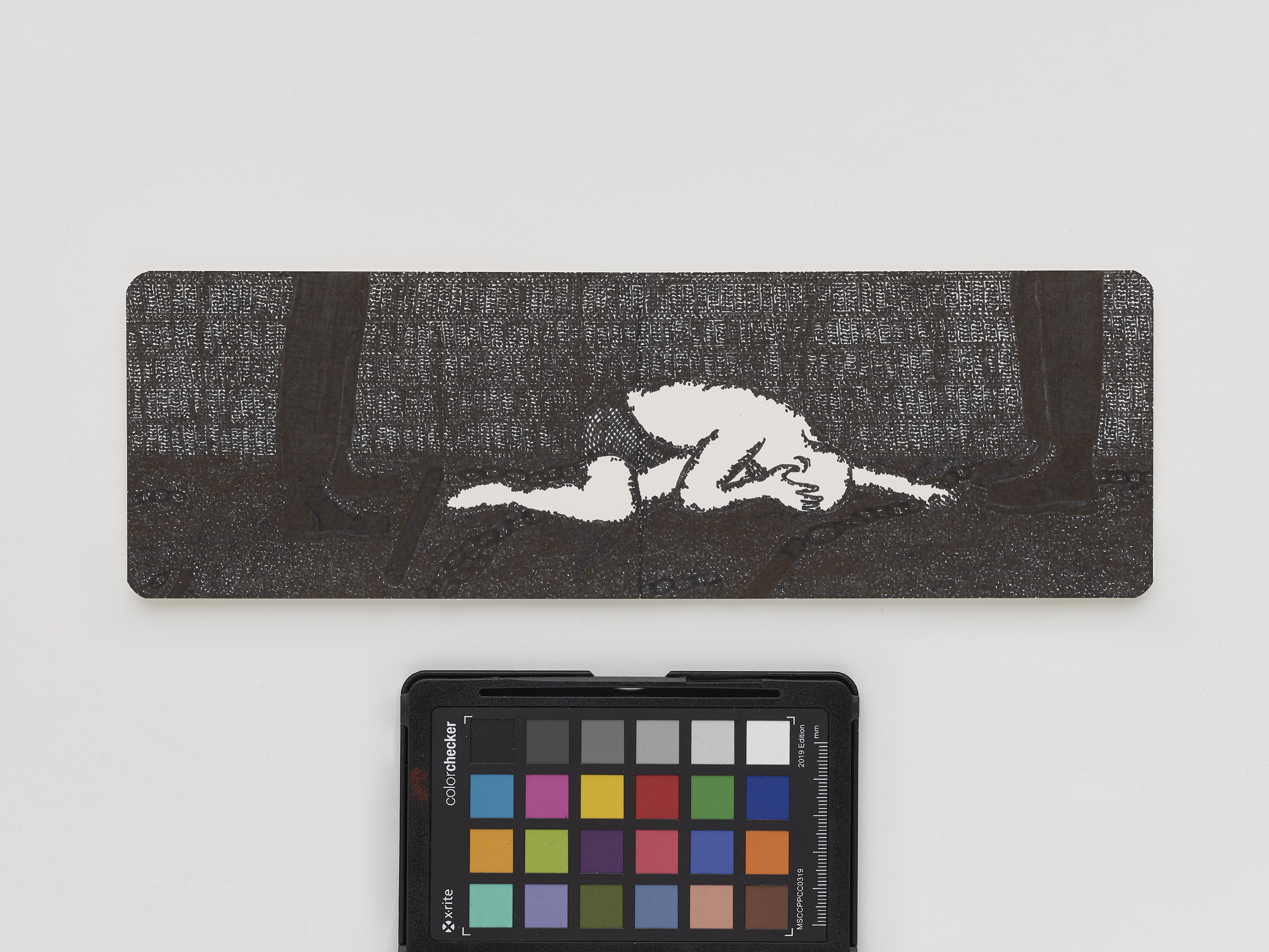

I drew M’s Story on paper that I extracted from pocket sized moleskine watercolour notebooks, scanning each finished drawing with a portable scanner before returning the folded page to the pad—the set up was easy to carry around in a bag or suitcase. This was only a temporary measure. I knew that the pages, with their sometimes scratched and burnt surfaces and folds down the middle, would need to be professionally photographed once I reached the end of my work.

I finished sketching the book in Lisbon where I was living, and I was preparing to have all the drawings photographed when the eruption of the Covid pandemic led the city and much of the world to shut down. I profited from the ensuing confinement to revisit my diaries and notebooks from my trip to Jordan in 2006, and pull them together into a written book, The Iraqi Suitcase, a mirror volume to M’s Story.

At the end of that autumn of 2020, I was offered the chance to borrow an apartment abroad for a few months and I travelled there with the sketches, hoping to have them photographed once the pandemic abated. A few days after my compulsory quarantine on arrival in the country, the borrowed flat was flooded and the authorities declared a lockdown that would last for months. I suddenly found myself with nowhere to stay, then, away from the capital, in a sequestered town where the constantly changing restrictive measures, shut and open borders, closed passport offices, twists of fate and eventually severe illness, rendered it impossible to reach anywhere where I had reliable options.

During those precarious months of housing for cash and promises and plans frequently broken, the sketches were traipsed around in a suitcase, wrapped for protection in two white sheets grabbed from the flooded flat, the suitcase at one point entrusted to a stranger. I began to reason that M’s story might never exist as a printed volume; if the suitcase were to be lost, I would need to make do with my temporary low-quality scans. I started to picture the book in more fragmented terms: the potential laying out of rough print outs in loose parts or strips on the ground, a form of fragile, unfinished paper film—a tale that could travel the world in a small box and be cheaply assembled and dis-assembled with minimal cost and fuss. And, the idea stuck. Hence, my decision to present M’s story in this way too.

Sketch of M‘s Story finally photographed (with colour checker).

7. If one is going to look at torture, perhaps the best way to do so is kneeling down

And the placing of strips on the ground was linked in my mind to two other things: The photos that I had seen of numerous books laid out on low tables or wooden pallet-like structures and sometimes directly on the pavement in Al Mutanabbi-street, the mythical book market of Baghdad, of which several Iraqis had spoken of to me with great love. (The street would be the site of a tragic suicide car bombing, on March 5, 2007, the target not only the approximately thirty dead and over one hundred injured book lovers and book sellers, but books, culture and community itself, people said. The date is still commemorated with readings around the world.)

Another image: the laying out of wares for sale on white sheets on the ground by groups of street vendors in Venice, the city from where I had set out to Jordan, in 2006, many of them undocumented African migrants, some employed by criminal gangs, who, when the Italian police would descend on the street to break up their trade and arrest them, would frantically sweep up their merchandise into the sheets and flee with their hasty bundles, scattering into the narrow side alleyways, their overflowing wares falling, sometimes, as they ran, leaving a trail of counterfeit bags, sunglasses, and trinkets on the paving stones in their wake.

When M told me his story, I found myself thinking back to that game of cat and mouse that I observed during the weeks I spent in Venice before travelling to Amman. How many, if any, of the running street sellers were carrying a hidden, untold story of torture? African migrants on their journeys to Europe were being were being tortured, thrown into solitary confinement or disappeared (and still are today) in the detention and trafficking centres of Libya, both by the authorities and the traffickers, and now the militias too. The survivors were deterred from ever speaking out or seeking justice by fear of reprisals and mistrust of the authorities.

8. Something homemade and incomplete

The finished sketches are uneven and my style changed with the years. Sometimes people with professional experience offered me advice on how to improve the drawings, recommending that I learn the rules of perspective or retouch details in Photoshop. But I ignored their suggestions because I felt that my way of depicting M’s story should remain close to the spirit of suddenly listening to him recount his tale in the small apartment, and to my spontaneous promise to retell it—not dictated by art or literature or a tradition. It seemed more true to the way in which M was forced to live inside his own head in the cell, for years.

I would like the reader to carry away with them the impression of something homemade and incomplete. If they reject the obscenity of the attempt to draw torture, I hope that they will still pose the question that I have been asking myself ever since I met M: if a stranger asks you to recount their experience of torture anonymously to the world in images, what should you do? For you cannot pretend that the American and British armies brought justice. There is no court, no documentation, no reconciliation commission, only a promise to tell that has been forgotten or kept.

A Looted Taji Camp

Abandoned Iraqi Republican Guard documents inside a looted and occupied Taji camp. Re-filmed from US soldier‘s online posts.

With many thanks to John Knight for eopy editing this text.

Footnotes

-

Mini DV was the format on which I had shot my preceding films, but my Sony TRV-900 cameras were now on their last legs, the images covered in burnt pixels that became evident when I filmed in low light, and the band of recorded tapes frequently chewed up when I tried to play them back.

Image Captions

-

TV footage of the first night of 'Operation Desert Storm', and the first American and Western strikes on Baghdad, January 1991 (The Gulf War 1990–91).

-

The end of 'Operation Desert Storm'. A helicopter shot of abandoned and destroyed retreating Iraqi army vehicles on The Highway of Death, April 1991 (Gulf War 1990–91).

Source

Waddington, Laura. “On Mirrors and the Making of M’s Story.” 8-page essay written in lieu of an artist’s statement for Laura Waddington’s website, May 2024.

Back to top