Delfina’s Cinema, Which Was in a Hurry

By Roberto Ellero

Translated from the Italian by Laura Waddington

Excerpt pp. 8–9 of the catalogue:

Delfina, smiling, was in a hurry. A thousand ideas, a thousand projects. Venetian of the world, Venetian in the world: a degree in History of Art in London, a strategic stint in New York, heart of the avant-gardes, and then many other places. Returning each time to Venice. It happened that one met her by chance, casually, on the street, in the vicinity of the Zattere. A brief recap of previous episodes. More hers than mine: I’ve been making a few things, you should take a look at them. Of course, you know that we have a new cinema space now? And then a small festival on the Lido, at the beginning of September, during the Venice Film Festival. You must come. Forget the red carpet, there is nothing to be won but it’s not bad… And in Venice, it really happened, maybe it still happens, that a casual encounter on the street becomes an appointment, a commitment.

Curious coincidences

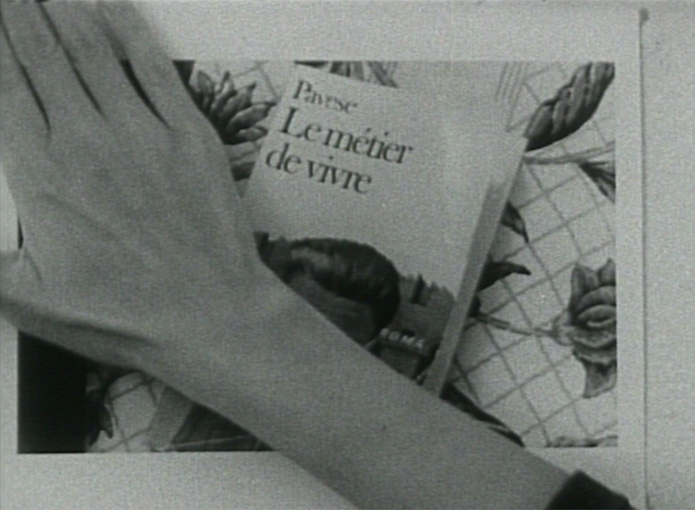

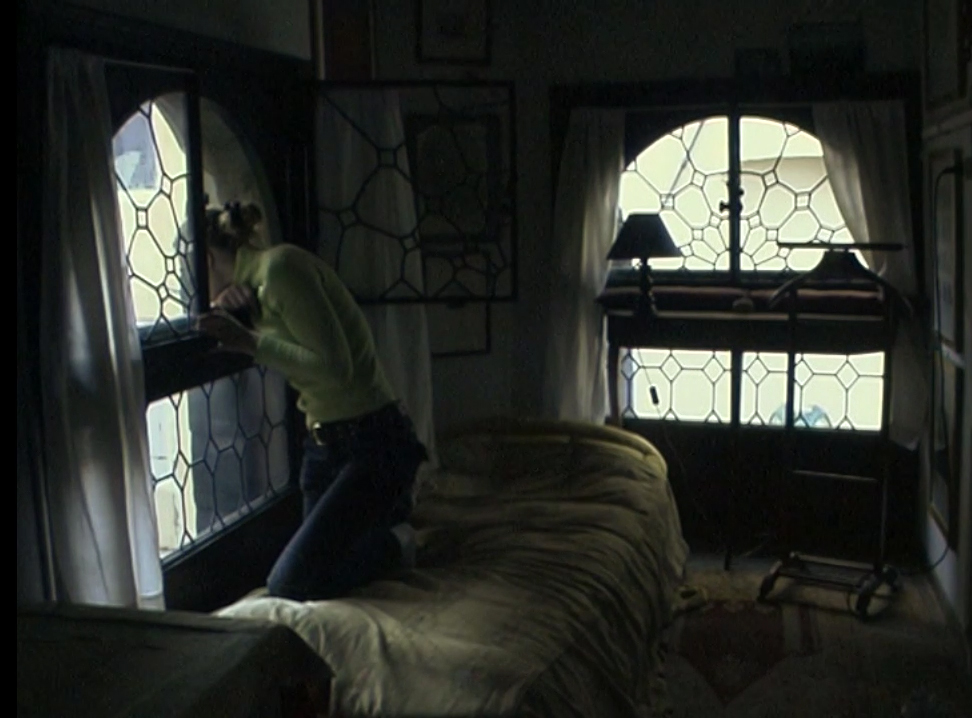

The world is small, even in New York, where Delfina Marcello took her first steps as a filmmaker at the beginning of the 1990s, within the milieu of independent, cinema. In 1992, she landed on the set of Laura Waddington’s film The Visitor, the story of a chambermaid who photographs the traces left by a guest … in the hotel room that she cleans each day: personal possessions, the first page of a diary, the cover of a French edition of Cesare Pavese’s This Business of Living.

Delfina was born in 1966; Laura, a London transplant, younger, in 1970. A friendship was born. And the genesis of the film, which the director traces back to a Venetian memory, is curious: “Once in a hotel in Venice, a chambermaid had gone through my things and recorded her voice onto my walkman. I wrote this story for her.” Even more unusual are the recollections of the encounter with Delfina: “We shot The Visitor in a weekend in a Manhattan hotel room, carrying the camera and equipment into the hotel, hidden in suitcases. The actress, Delfina Marcello, whom I had picked to play the chambermaid for her beautiful face and a mystery about her, turned out to have come from Venice. At the end of the shoot, she told me that we had already met. Years before, while studying in London, she had worked as a coat check girl in a restaurant and had always remembered a shy school girl, who had handed her a coin and smiled. I didn’t recall our encounter but it was, indeed, the restaurant, where as a teenager, I used to meet my father. That was my first introduction to the strange way in which filmmaking weaves in and out of life.” Delfina, whose first role is therefore that of a chambermaid, after working in a London restaurant while studying at The Courtauld Institute of Art, will go on to work as Waddington’s assistant on The Room (1994) in which she will, also once again, play the role of a chambermaid, and [assist her in preparing] Zone (1995), to then avail herself of Waddington’s collaboration (camera assistant) on the occasion of Prayer for Violence (1994-2003) Life events, destined to produce strange echoes, and returns of time…

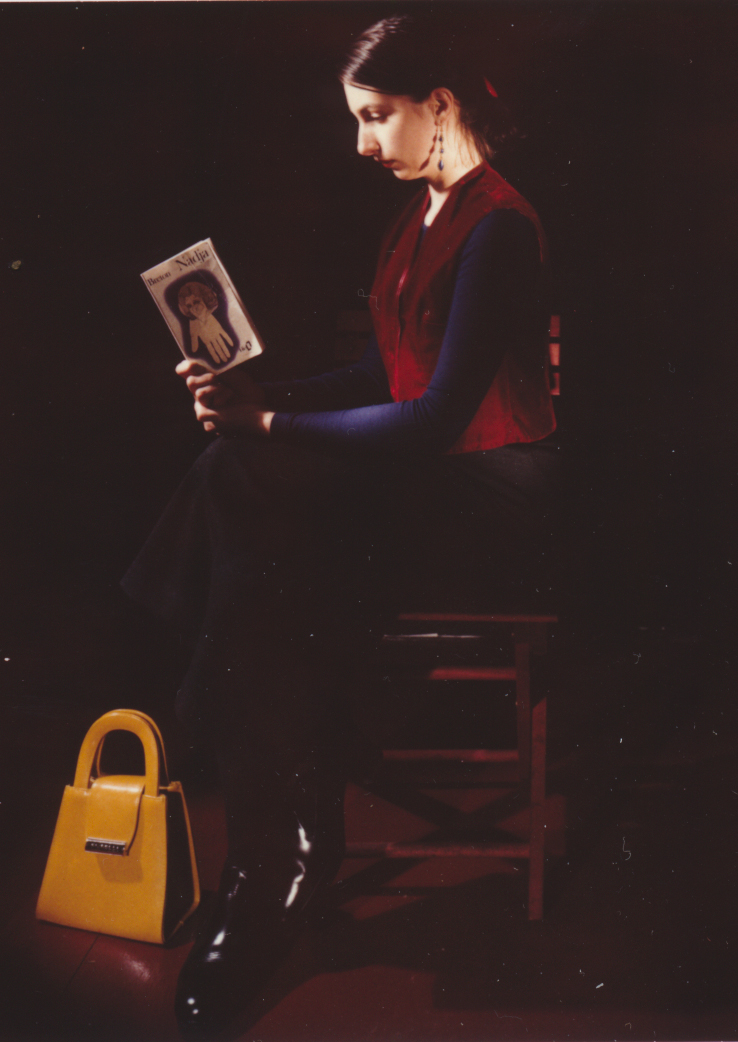

Top left to right: Delfina Marcello in The Visitor (1992) by Laura Waddington. Bottom left to right: Delfina Marcello and Federico Pacifici in The Room (1994) by Laura Waddington.

Just to start

Delfina Marcello’s directorial debut came the following year, 1993, with Bon Appetit, still in New York, the start of a career that would count eleven titles in just under twenty years, in addition to collaborations with other directors (among them Momoyo Torimitsu for Miyata Jiro, 1999, and Business in Paris, 2000, and Koh Yamamoto, the young man of the finale of Prayer for Violence, for The Masturbating Ego Show, 2010). It is acknowledged that her filmmaking is part of a wider artistic and performative practice. particularly photographic. An inviting title, intriguing and even somewhat ironic, in which a “Buñuelian” eye, fortunately not cut, peeks out from behind a curtain, at first in shadow and then illuminated, the entire right side of a female face, attracted and desirous…

(End of excerpt)

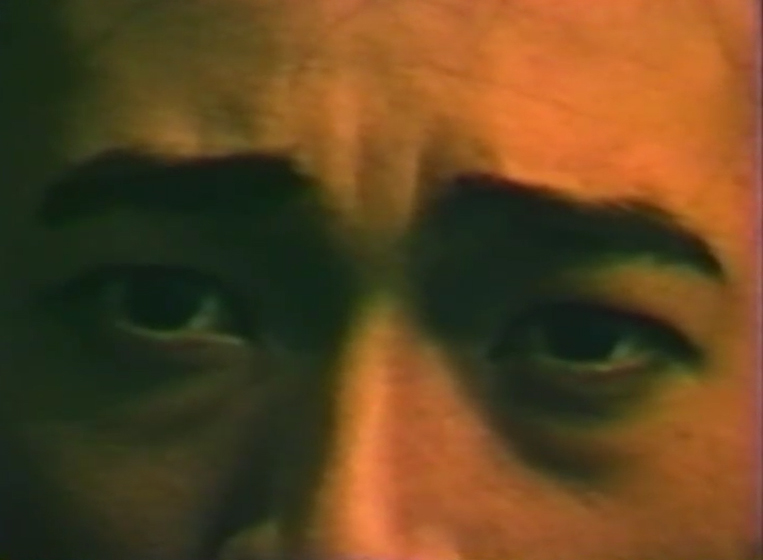

Koh Yamamoto in Prayer for Violence (1994-2003) by Delfina Marcello.

Excerpt pp. 15–19:

Minimal diaries, domestic interiors

Interior shots of a palatial apartment from a bygone era. Details of antique furniture and then of wrinkled sheets and pillows. A tight close-up of a young woman busy with housework. A few moments of thoughtful pause. On the wall, portraits of a beautiful lady, also from another era, young and elegant. The young woman is perhaps finishing her shift, getting ready in the bathroom. She is reading or leafing through a book, in French, about a great painter, Eugène Delacroix à Paris. There is underwear to be tidied away. She writes a letter, seated at the desk of the home. In another room, her colleague helps the elderly mistress of the house to get dressed, then they play cards, while the radio plays fashionable songs. Now there is a male voice announcing something. The lady becomes agitated, shuffles the cards. We find her lying in bed, being fed by the caregiver. She struggles to eat, her gaze lost in the void. The other young woman waters plants on the balconies. We recognize Venice. Indeed, straight after, the lens frames a vaporetto stop belonging to the public transportation company and the arrival of a vaporetto of the line 3 (line temporarily introduced to protect residents from the tourist invasions: a fiasco, but the film could not have known that). On board a vaporetto, we recognise the young woman who was watering the plants. She has finished her shift and is on her way home. A prolonged scene. Meanwhile, her colleague helps the old lady to get dressed and to stand up. A song on the radio – Adamo’s La notte – inspires an impromptu dance between the two. A small moment of joy. The elderly lady is now watching TV. The carer is busy with more cleaning, the washing machine. The young woman from earlier on has reached Piazzale Roma. She has boarded a bus to Mestre. At the via Righi stop, she greets someone, smiles. Delacroix à Paris (2009) is a three-character portrait: the two domestic helpers (one of whom, Liudmila Plămădeală, is destined to fully occupy the scene in subsequent works) and the elderly lady, Matilde Terzuoli Marcello, architect and prominent figure in the city’s cultural landscape, above all the director’s mother, portrayed with affection, it is to be believed, though in one of those phases of existence about which the memory becomes painful. That’s life. It seems that even Delacroix, who had immortalized the revolution on the march, the quintessential romantic of French pictorial mastery was no longer himself when he returned to Paris after savouring the pleasures of the Orient. But these are only conjectures, arising from an eccentric and fancifully evocative title.

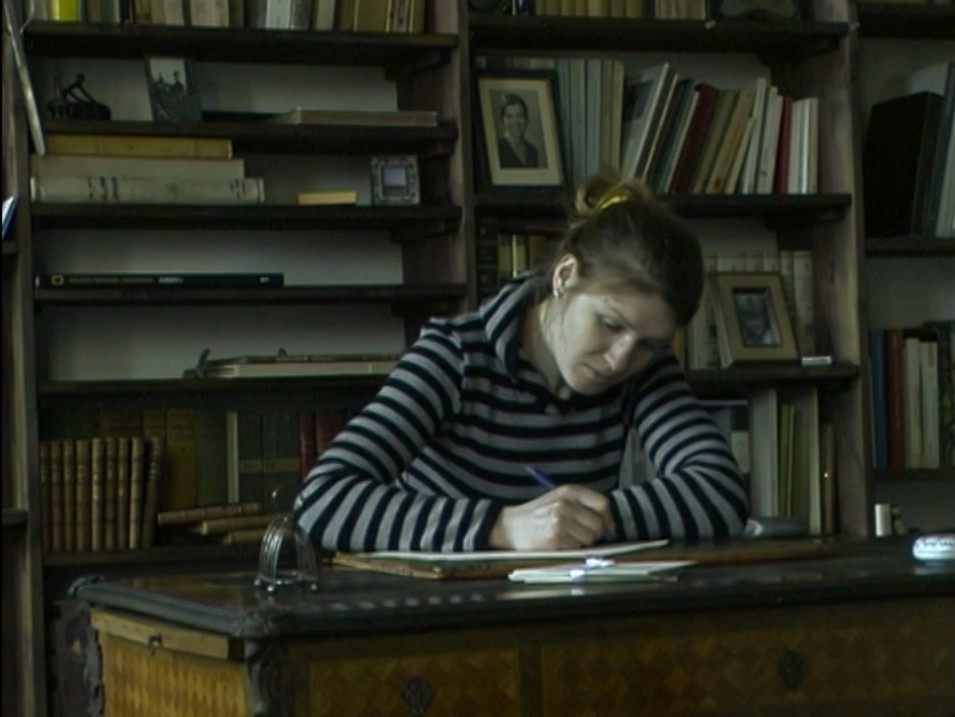

Liudmila Plămadeală and Matilde Terzuoli Marcello in Delacroix à Paris (2009) by Delfina Marcello.

The lapping of water. We are in the same period On Water (2009). A young woman in a bathroom, (Liudmila Plămadeală again) brushes her teeth, dries her hair. She picks up her things and leaves the house, reaching Piazzale Roma by motoscafo [small water bus], passing through Scomenza. She drinks a coffee. We move to another apartment, sheets and pillows to arrange, a bloodstain. The young woman is back in a bathroom again, scrubbing intently. The bloodstain, probably. Evening, a vaporetto stop, the young woman is waitingI. Another interior, another bathroom. The young woman applies makeup in front of the mirror, then tends to her hands. An exterior shot. New taps are turned on. A penis, marked by time, in close-up. A female hand cares for it, washes it. A furnished corridor, a chic apartment. Off-screen voices in English. But they are not those of the homeowners, we will never see them (or perhaps we do, at the end). The voices are coming from a movie that the girl is watching on television. A romantic comedy. Night, a vaporetto. The young woman, elegant, is dressed in black. We are passing through Ca’ Vendramin Calergi, the Casinò, San Marcuola, almost like in that very first film by the Lumière brothers, who at the dawn of cinema invented, in Venice, the tracking shot by simply placing the camera in a vaporetto. Back to an interior, a conspicuous pearl necklace around the young woman’s neck, period music. Settecento and its environs, violins, she in close-up, from behind. Then a wide shot of the piano nobile room. She, lying down, en déshabillé, speaks on the telephone with her mother. In Romanian or Moldovan. The usual things from afar: how are you, the weather, did you do that thing, how do you feel, what do you want me to say, that’s all I have to tell you… Still shots of men lying in bed, motionless, asleep, filmed from the waist down. Men of various ages, builds, degrees of vitality. Who are they and what relationships do they have with the young woman? We’ve seen her go from house to house without really understanding what her job is. Domestic helper, but of what kind? Let’s say a femme de compagnie for solitary men, the sleeping ones, to be precise… Phenomenology of jobs that exist and do not exist, contemporary domestic wanderings, perhaps in the most ancient and commonplace of trades Alienation, doubts, and that compulsive water always present, starting from the title. A necessity, perhaps a sporadic need for cleanliness.

Liudmila Plămadeală in On Water (2009) by Delfina Marcello.

Finally, Joy (2011), whose protagonist is still Liudmila Plămádeală (in the credits from now on simply Plamadeala, written the Italian way). Having shed the elegant clothes worn in On Water she now looks much more like the somewhat sad girl from Delacroix, whom we left on the bus to Mestre. An anonymous apartment block on the mainland, we see and hear cars. Modest interiors, working-class yet dignified. The young woman is preparing food. The television is on; there’s the horoscope of the day, the ubiquitous Magician Fox, capable of expounding on Capricorn better than a philosopher on metaphysics. Those born under that sign are naturally called on to put their best feet forward. And then Scorpio, another monologue but trailing off, as the action shifts from the kitchen to the other rooms. A short phone call home. Now the young woman moves on to other household chores. Lunchtime arrives. Perhaps it is Sunday. At the table, with her, a couple, probably fellow compatriots. They watch television, all together. The young woman appears tired, her face even sadder, almost resigned now. Cut. More vivid images appear of festivities, a Christmas of bygone years, amidst family. Memories of joy.

Cinema of Reality

Shot in close succession, between 2009 and 2011, Delacroix à Paris, On Water, and Joy share many similarities, starting with the presence of the same protagonist, her origins, her job profile, and the alienation that arises from being where she shouldn’t or wouldn’t want to be. An authentic trilogy, or perhaps three phases of a single film, leaving the spectator free to connect up identities and life trajectories. Because Joy could also be the day off of the young woman who cleans in Delacroix, and perhaps also, if one wishes, the other face of the uninhibited young woman in On Water. But beyond the convergences suggested by the same actress, they could also be wholly distinct portraits of three Eastern European women employed in the new domestic roles widespread in a country of old people, ever less self-sufficient. Cinematic time invariably tends to be rarefied and almost coincides with real time, tranches de vie, updates of certain features of cinema verité already in use in the 1960s. These are, however, the last known works of Delfina Marcello, who left us prematurely in 2017, a little over fifty years old. In such cases, what was originally not intended to be “testamentary” tends to be regarded later as such: after all, we don’t know so well in advance when our time will come. Certainly, this triple female portrait, minimalist and wordless, as her works often are, expressions of a poetics that would have pleased Zavattini, whose theory of “pedinamento” encouraged the director’s full immersion in the subjective dimension of storytelling: highly personal, devoid of didactical frills and even more so ideological ones, this precisely the most suitable hallmark by which to define the “cinema of reality” that burst onto screens in the new century, a notion perhaps still vague and imperfect, yet nevertheless useful for understanding the modes of filmmaking that have definitively abandoned the alleged objectivity of documentary and the mere versimilitude of fiction, instead taking on the burden of reality as it is. This phenomenon can also be observed in certain literary narratives, where the narrator willingly involves him or herself in the events narrated. In the case of our author, the explicit remains phenomenological in nature, it does not entail emotional entanglements, simply because the director is not seeking them out or provoking them, while the degree of implication remains willingly vague, suspended, incomplete. The cinema of Delfina Marcello has always been allergic to explanations, and even more so to ‘ethical’ fabrications. It certainly selects reality, presents its features without deception yet works rather through suggestions, traces, significant fragments. One is struck, when it comes to the themes and figures of the trilogy, by the singular circularity of a return: female ‘service’ figures, exactly as in the first roles played by Delfina for Laura Waddington and recalled by her in the recollection of the first meeting. Filmmaking that weaves in and out of life, she said.

Liudmila Plămadeală in Delacroix à Paris (2009) by Delfina Marcello.

Solitude

We do not have too many critical interventions about the cinema of Delfina Marcello, who lived on the margins of officialdom, like a substantial portion of the experimental cinema world of yesterday and today. In the press documentation of the exhibition at the Ikona Gallery, we come across a profile by Alfredo Sigolo: “ … the originality of Delfina Marcello, resides in her ability to conduct analytical investigations into historical facts and current events, deconstructing and reassembling them to recreate unprecedented visions and allegorical sequences of great allure and beauty, in which reality appears to run aground and become irrevocably shipwrecked in the abyss of conscience: an alchemical formula that is a clear blueprint for aesthetics’ (from the catalogue of the exhibition On Air, Galleria Comunale d’Arte Contemporanea di Monfalcone, 2004). Alchemical formula, abyss of conscience: these are notions that certainly capture that mysterious, somewhat cryptic, highly conceptual and therefore encoded character which defines the director’s works, in which every frame can conceal questions that are destined to remain as such, especially when it comes to eventual autobiographical references known only to the author and perhaps to the few who shared her intimate world. It is therefore difficult to venture down such paths for they would soon interrupt us or lead us astray.

And if we have lingered, title by title on a textual reconstruction of her works, it is precisely because no synopsis will ever be able to condense their actual complexity into the couple of ‘plot’ lines invariably required for the speedy preparation of theatre programs. The part often presented in place of the whole, and therefore also the employment of synecdoche alongside the many other rhetorical devices visually explored by Delfina, but along with derailments that perhaps lead elsewhere, hinted at and unexplored paths, visual cues of other possible narratives, not necessarily traceable back to the main story that the director is telling. A complex and articulated visual experience, multifaceted, polysemic, where the research remains inexhaustible. A trait that unites the female figures of the trilogy, and upon closer inspection also a good part of the characters brought to the screen before this, is the condition of solitude that defines them, the absence of relationships and emotional ties, social motivations and perhaps even personal ambitions, solitary and suspended characters, who at best escape into dreams, into recollections of a happy memory now irrevocably distant in time. A condition that can certainly well apply to the sensibility of the author, whom we have remembered, since her first performance in Laura Waddington’s film The Visitor: that Hopperesque ending that presents her in complete solitude at a bar table, an astonished look, while through the glass windows that envelope the corner spot, stream the headlights of the incessant traffic weaving through the streets of Manhattan.

The Primacy of Vision

Delfina was in a hurry, but not without stopping to reflect. And her filmography punctuates these reflections, with a consistently disruptive visuality. Words and speech – when present – do not shine; they have a role and a space that is certainly less pregnant than the visual, which knows how to be both stillness and movement, literal meaning and more often figurative, with elliptical processes that engage the spectator in the construction of their own personal interpretation and dimension of enjoyment (exemplary in this respect is Fur, which remains suspended in its eloquent but, at core, deliberately ambiguous metaphorical dimension). From the expressionist and exuberant theatre of Bon appetit to the minimal diaries of Delacroix à Paris, On Water, and Joy, almost twenty years pass, the span of a lifetime in the case of the director, and what was initially amused provocation, rich in implications and references, an exhibition of the body and desire, becomes in the end an almost mimetic adherence to minor lived experience, essential even Bressonian in its work of subtraction: the young women of the trilogy as ‘models’. The pop experiences (Prayer for ViolenceL and especially Enjoy) display a playful vitality that never abandons an ironic (and also critical) perspective on American life (the practice of daily violence, the commodification of sexual fetishes), shared for some time by the author during her stay in New York, while the return to Europe seems to open up new unpredictable scenarios: the narrative temptation of Il bivio, which could herald a transition never realized to feature-length fiction, and the vein of the so called ‘documentary-style’ work, which began with Metalzerodegrees and continued with Inside. Luce e movimento, this last title—as mentioned—already ‘infiltrated’, in its second part, by signs of the nouveau réalisme that the director was practising simultaneously in the trilogy. Central to, and also strongly representative of the profoundly authorial character of Delfina’s cinema, is the small experiment in self-portraiture that is Love Accessories, which we have labelled an ‘interlude’ precisely because it marks an overtly personal pause between a before and an after in the author’s work. On the one hand, there is the film-making, the pull of the sirens of video art and experimental work; on the other, more oriented and consistent filmic practices which are aimed at a more colloquial relationship with the public, with the critics, with reality itself. There is no retour à la normale, however, the style remains highly personal, as does the constant presence (right from the titles) of a certain propensity for understatement, irony and reference to the unsettling other, a way of being that is almost a personal trademark, in itself. Let us rather say the possible opening to new expressive horizons, if only there had been time. For this reason, too, there remains a profound regret for what more Delfina could have offered us, perhaps succeeding once again in amazing us. She leaves us a filmic work that is necessarily interrupted, partial, still and always in progress, yet extremely rich, diverse, endowed with a consistent commitment to the primacy of vision. And it is for this journey of hers that we are deeply grateful.

Prayer for Violence (1994-2003) by Delfina Marcello.

Essay from the catalogue ‘Love Accessories, Delfina Marcello’, compiled and produced by Ewa Gorniak Morgan, Margherita Fabbri, Lorenzo de Castro, and Vittorio Urbani for the exhibition of the same name, curated by Vittorio Urbani and produced by Nuova Icona in collaboration with the Scuola Internazionale di Grafica Venezia.

The exhibition was held at Oratorio di San Ludovico, Venice, Italy, from 2 to 30 September 2022, in parallel with the exhibition EX VOTO (also dedicated to Delfina Marcello’s work), curated by Francesco Pandian at Galleria Artericambi, Verona, from 17 September to 20 October 2022. Both exhibitions were organised with the agreement of Pietro Marcello.

Reproduced with kind permission of the author, Roberto Ellero. The copyright for this text and all images—except those from Laura Waddington’s films—remains with the respective rights holders.

With gratitude to all involved, in the shared hope that Delfina’s work and legacy will continue to reach new audiences.

Source

Ellero, Roberto. “Il cinema di Delfina, che andava di fretta.” In Love Accessories: Delfina Marcello Catalogue, edited by Ewa Gorniak Morgan and Margherita Fabbri. Venice: Nuova Icona and Scuola Internazionale di Grafica, 2022: pp. 8, 18. Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same title, produced by Vittori Urbani and Nuova Icona, in collaboration with Lorenzo de Castro and others, at Oratorio di San Ludovico, Venice, September 2–30, 2022.

Ellero, Roberto. “Delfina’s Cinema, Which Was in a Hurry.” Translated from the Italian by Laura Waddington for this website.

Back to top