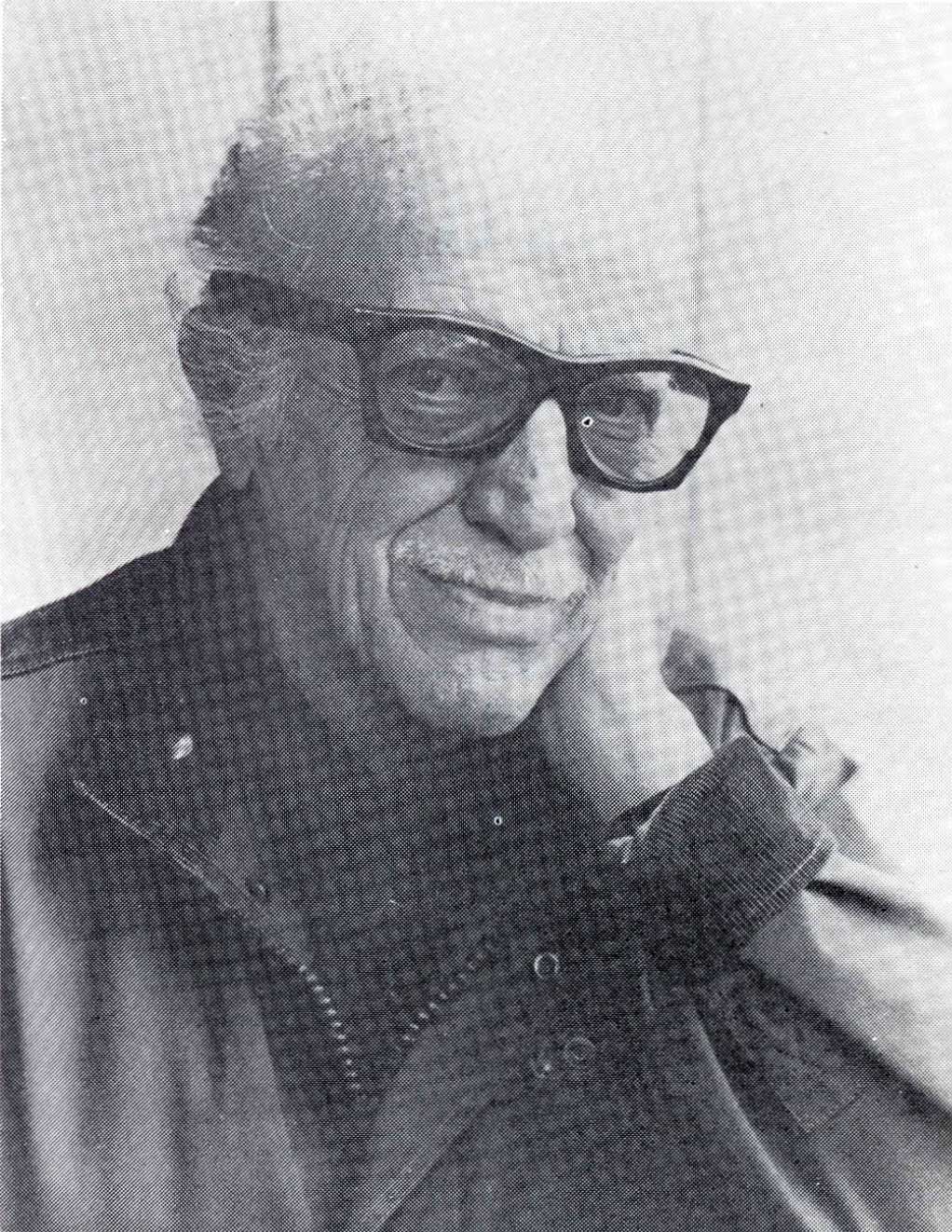

From Shadows and Mexican Skies: An Interview with Gabriel Figueroa

By Laura Waddington and Walter Rippel

This interview with Gabriel Figueroa took place during his trip to New York for Master of Shadows:A Tribute to Gabriel Figueroa, at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, in September and October 1992. Conducted in English, it was later translated into Spanish by Walter Rippel, who added the introductory notes. Since the original English recording is lost, I have retranslated the Spanish version, which was published in El Amante Cine (Buenos Aires) in February 1993 , back into English. (LW)

*

Born in Mexico City in 1907, Gabriel Figueroa has worked as a cinematographer on more than 250 films. Among his vast oeuvre, we recall: The Fugitive (in collaboration with John Ford); Los olvidados, Nazarin and The Exterminating Angel (by Luis Bunuel); The Night of the Iguana and Under the Volcano (directed by John Huston); and the remarkable series of films created in the 1940s alongside the Mexican director Emilio “El Indio” Fernández: Flor silvestre, María Candelaria, La perla, Enamorada, Río Escondido, Salón México.

We interviewed Gabriel Figueroa in New York, where he was attending the tribute organised in his honour by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Mexican Film Institute.

GF: Gabriel Figueroa

Q: Laura Waddington and Walter Rippel

He is a small man, a passionate conversationalist:

GFI miss black and white cinema. It is intrinsically artistic and more powerful. One could create volume and depth in the image. When filming in colour, the colours themselves provide the contrast, and define the separation of space. Let me say this: Picasso wouldn’t have achieved the same social and artistic impact with Guernica if he had used colour. For my part, I grew accustomed to photographing in black and white, creating what I call murals of light…

Q“They are living murals,” declared Diego Rivera, one of the Mexican muralists, and “his images travel the whole world” [describing your cinematographic work].

GF Oh yes! They, the Mexican muralists, are great friends of mine and have profoundly influenced my work. From Orozco, I took black and white; from Rivera, colour and composition; and from Siqueiros, curvilinear perspective. Naturally, I have had other influences: German Expressionism, Eisenstein, the striking figures of Goya, and the deep-focus cinematography of Gregg Toland [the director of photography for Citizen Kane].

Q Is there anyone among your peers who has significantly influenced or impressed you?

GFIn Mexico, we have one, Angel Goded, who is quite good. And Bergman’s cinematographer, what’s his name? Sven Niwisky? [amidst laughter, jokes about always struggling to pronounce his name]

Q“Nykvist?”

GFYes! That’s him. He is extraordinary. I heard that when he was making the film based on a novel by Proust [Swann in Love by Volker Schlöndorff], he spent an entire year studying the changing light at the location. The transposition of Proust’s words into his own imagery – an extremely challenging task for us cinematographers – was brilliant.

QWe touched on the subject of literature and film adaptations. You have mentioned that the biggest challenge for Mexican cinema is the lack of good scriptwriters.

GFIn Mexico, we lack good screenwriters. And if someone wants to acquire the rights to a work by, say, Carlos Fuentes, Vargas Llosa, or García Márquez, they demand a million dollars. Who in Mexican cinema can afford such a fortune?”

QHave you ever written a screenplay yourself?

GFI have only written a synopsis. Its title is Old Havana. It is about the life of a close friend of Batista and the political upheavals in Cuba. I have entrusted several screenwriters with the writing of the script, but, to this day, it remains unfinished.

QYou chose the stories that you worked on as a cinematographer very carefully.

GFThat’s because without a good script, there can be no good film. Let me tell you about my experience with John Steinbeck. In 1950, he came to Mexico with Elia Kazan to show me his script for Viva Zapata. I read it, and I didn’t like it. It was a sort of Viva Villa! It didn’t explain any of the reasons that drove Zapata to take up arms. I spent three days with them, and on the third day, I told Steinbeck: ‘You’re making a mistake. You don’t show why Zapata fought. And that scene with the verses—what? Zapata and poetry? That scene should be cut from the film.’ Then, Kazan called me and said: ‘You have the nerve to argue with Steinbeck?’ ‘One thing is certain: I know more about Zapata than Steinbeck does,’ I replied. Eventually, they hired another screenwriter to rewrite the script. It was much better, but it still didn’t convince me. I decided not to shoot the film.

QOn the other hand, you appreciated the adaptation of Graham Greene’s novel, The Power and the Glory, in The Fugitive, directed by John Ford?

GFYes, it was a good script. However, I think it lacked something: the priest (played by Henry Fonda) should have been portrayed as an alcoholic. This is made very clear in the original novel but it‘s not reflected in the film.

QWhat was your collaboration with John Ford like?

GFFord realised that my method of working was different from what he was used to in Hollywood: once the director had chosen the camera position, I would create the composition and lighting that I believed the shot demanded, then wait for the director’s approval. Ford found this system—one that Emilio Fernández (Fig.1) and I had always used—interesting and adopted it.

But it was different with Buñuel. He knew exactly what he wanted in each shot. I focused solely on defending my craft through lighting. In this area, neither the director nor anyone else could interfere. In every film that I’ve worked on, I’ve always been the master of light.

QDid you ever feel that Buñuel’s approach restricted you in any way?

GFNot at all. I had immense respect for Buñuel, he was an extraordinarily intelligent man. I remember during the filming of Los olvidados, he gave me a camera position, I composed the image and asked him to examine it. He looked through the viewfinder and said to me: ‘That’s a beautiful landscape, Gabriel. But I have a better suggestion: why don’t we turn the camera around 180 degrees and film those dirty geese flapping their wings in the mud?’ [laughter]

QI understand that your collaboration with John Huston wasn’t quite as serendipitous…

GFDuring the filming of Under the Volcano, Huston could only move around in a wheelchair. So he made the decision to shoot the entire film with the Steadicam system, which turned out to be a huge mistake. It’s similar to using a zoom, you shouldn’t overdo it. Also, we had a camera operator; I wasn’t handling the camera myself, so I lost control of the photography. My only line of defence was the lighting. On another occasion, Huston asked me to work with him on a film about the Impressionists [Moulin Rouge], but I turned down the offer. I didn’t feel capable of shooting a film entirely “out of focus”—my style is expressionist. Over time, I came to realise that my decision was the right one. Huston carried out countless tests to achieve an impressionist atmosphere, but he only succeeded in conveying it in one sequence: the can-can dance. As for Night of the Iguana, it’s a good film and an excellent adaptation of Tennessee Williams‘ work. However, I only feel responsible for 30% of the film’s cinematography, as it was Huston who decided on the composition of most of the shots. Curiously, it was the only film for which I was ever nominated for an Academy Award in Hollywood. Huston also asked me to shoot Prizzi’s Honor, but unfortunately I was denied the papers to work in the United States.

(Referring to his retirement, Figueroa explains that it was partly due to fatigue and partly to disillusionment. “The scripts they offered me didn’t interest me. They proposed that I shoot Rambo 2, but I declined.”)

QOne final question: You served as Secretary-General of a division of the Mexican Union of Cinema Technicians in the 1940s, I believe? What has been the relationship between cinema and politics in your life?

GFI have never let politics interfere with my work. I do not belong to, nor have I ever belonged to any political party, either in Mexico or abroad. I joined the Union because the Central de Trabajadores Mexicanos (C.T.M.), which we all belonged to before separating from it, was controlled by gangsters, and it was absolutely vital to fight them. I also participated in demonstrations where students or workers were demanding fair rights. During the miners’ strike in Coahuila, which we lost, I contributed money and ideas. I was anti-Franco to the point of refusing to shoot any movies in Spain. On one occasion, the Mexican director Roberto Gavaldón sent me the following telegram: ‘Good script, with Dolores Del Río and Jean Gabin. To be shot in Madrid. I’ll direct. State your conditions for shooting the movie.” I replied, “When it comes to good friends and good stories, I have no objections. As for filming in Spain, I have only one condition: remove Franco from the throne!”

Translation into Spanish: Wa1ter Rippel, November 3, 1992

Translation back to English: Laura Waddington 2024

Image Captions

-

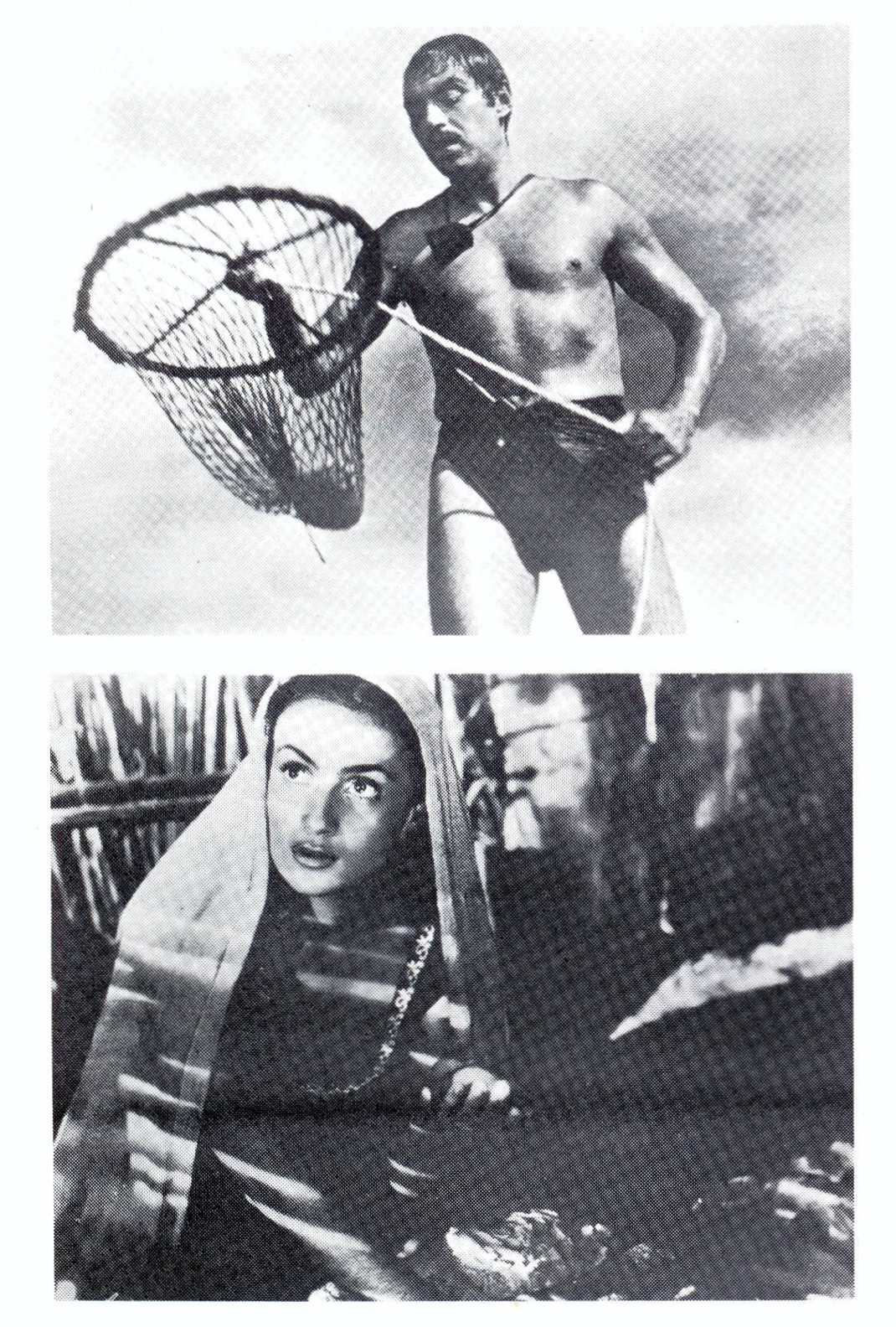

'La perla' by Emilio Fernández (1947). Photo scanned from 'El Amante Cine', no. 12, Buenos Aires, November 1992.

Source

Waddington, Laura, and Walter Rippel. “Fotografía: De sombras y cielos mexicanos, entrevista a Gabriel Figueroa.” Translated from the English by Walter Rippel. El Amante, El Amante Cine, no. 12, Buenos Aires, November 1992: pp. 42–43.

Back to top